One day, I hope many years hence, I plan to write a short biographical sketch of the great Father Alfred J. Harris, for many years the pastor of Saint Mary, Mother of God, in Washington, D.C. In preparation for this task, I have compiled a small index of material: reminiscences, anecdotes, quips, stray remarks from sermons (“On the annual Cardinal’s Appeal,” “On watching television,” “On Obergefell,” “On substitute Last Gospels,” “On Thomas Merton,” “On disliking Christmas,” and so on).

One of my favorite Father Harris stories involves friends of mine whose oldest daughter was preparing for her first Holy Communion. In those days it was the custom for parents at Saint Mary’s to bring their children for an interview with Father Harris, who would attempt to determine whether the child understood the nature of the sacrament. (There was, thank goodness, no formal religious education program.) But upon arriving at the rectory, instead of finding herself subjected to a detailed oral examination on the Baltimore Catechism, the girl discovered that Father Harris wanted to chat, mostly with her parents. These tales have a way of growing in the telling, but as I recall he talked for more than half an hour about various subjects—the state of Maryland, the best place to buy watermelon, his sister—before suddenly asking the girl: “So, after the consecration, does it stay bread?” This was too much. After thirty or so minutes of feverish anticipation, she could only respond by shouting, “NO, FATHER, IT’S JESUS’ BODY!” With this answer Father Harris expressed himself satisfied, and the girl received Our Lord for the first time the next Sunday. (These tales, as I say, have no doubt grown somewhat, but if there were any follow-up questions, I am not aware of them.)

I share this story not simply because it is amusing (or because it tells us something about the sociology of some Latin Mass parishes, though it does) but rather because my friends’ poor daughter—who could, of course, have recited the relevant answers from the catechism under conditions of equanimity—understood something that is evidently beyond the reach of learned professors of theology.

Not long ago Another Publication ran an essay by one Monsignor Kevin W. Irwin, apparently a professional “liturgist,” who argued that Catholics are wrong to regard the Blessed Sacrament as “the body of Jesus” rather than as “the body of Christ,” as if the two were somehow distinct. In defense of this quasi-Nestorian proposition Monsignor Irwin cites the decrees of Trent and other conciliar pronouncements in which phrases such as “the body of Christ” appear; he also attempts to draw attention to the general paucity of references to Our Lord’s personal name in formal theological writing.

Monsignor Irwin’s attempt to adduce evidence for his position from the infrequent appearance of “Jesus” in the decrees of ecumenical councils and the Missal is his first problem. His contention is historically illiterate. It is not a desire to separate Our Lord’s person from, well, who knows, which explains the wordings of the Tridentine and other formulas but rather the observance of a pious custom known in virtually every age and clime. Until very recently Christians have always refrained from using His first name (which, Saint Paul tells us, we should never utter without some act of physical reverence) except in certain highly specific contexts—e.g., scriptural quotations, certain prayers such as the Fatima petition and the Litany of the Sacred Heart, and, pace Monsignor Irwin, the Roman Missal. (One well-known exception to this rule is small children, of whom Our Lord was so solicitous, and from whom references to “Jesus” have a tender simplicity that is not at all irreverent.)

Far more serious than Monsignor Irwin’s baffling history, though, is what I take to be the actual implication of his position that the Blessed Sacrament is not “the body of Jesus” but the “body of Christ”:

To describe the Eucharist as the “body of Jesus” or “the real presence of Jesus” would be too limiting to the historical body and earthly reality of the Word made flesh and the incarnate Son of God. The “body of Christ” refers to the entirety of the mystery of the totality of Christ: his whole earthly ministry and also his suffering, death, resurrection and ascension to the Father’s right hand to intercede for us in heaven. The Eucharist is the real presence of this body of Christ, not Jesus only.

What distinction is he attempting to draw between the “historical body” and “the totality of Christ”? Is it a kind of dyophysitism in which the mere “earthly reality” is somehow separate from “the mystery”? Is it meant to draw some kind of meaningful contrast between the Divine Person and His actions (“his whole earthly ministry and also his suffering, death, resurrection and ascension to the Father’s right hand”)? The mind reels.

Having attempted to distinguish (apparently on the basis of historical misunderstanding) between “the body of Jesus” and “the body of Christ,” Monsignor Irwin proceeds to tell us what he means when he says that the “the Eucharist is the real presence of this body of Christ.” At one point, he quotes Mysterium fidei, in which Paul VI reminds us that Christ “is present in the Church as she performs her works of mercy” and “as she preaches the Gospel which she proclaims as the word of God, and it is only in the name of Christ, the Incarnate Word and by His authority and with His help that it is preached.”

This is certainly true, just as it is true that the Church herself is the mystical Body of Christ. But Monsignor Irwin (despite his bizarre references to Latin verbs) is using “present” (and by implication “body”) equivocally, and, I think, knowingly here without realizing how unintentionally hilarious the consequences of his position are. By insisting that in the “the body of Christ” (as opposed to the body of a somewhat related historic person called Jesus) the Real Presence is the same kind of presence that Paul VI means when he refers to Christ’s being “present” in the Church and the actions of the faithful, what he seems to be suggesting (again, no doubt unintentionally) would be rather funny if it were not sacrilegious.

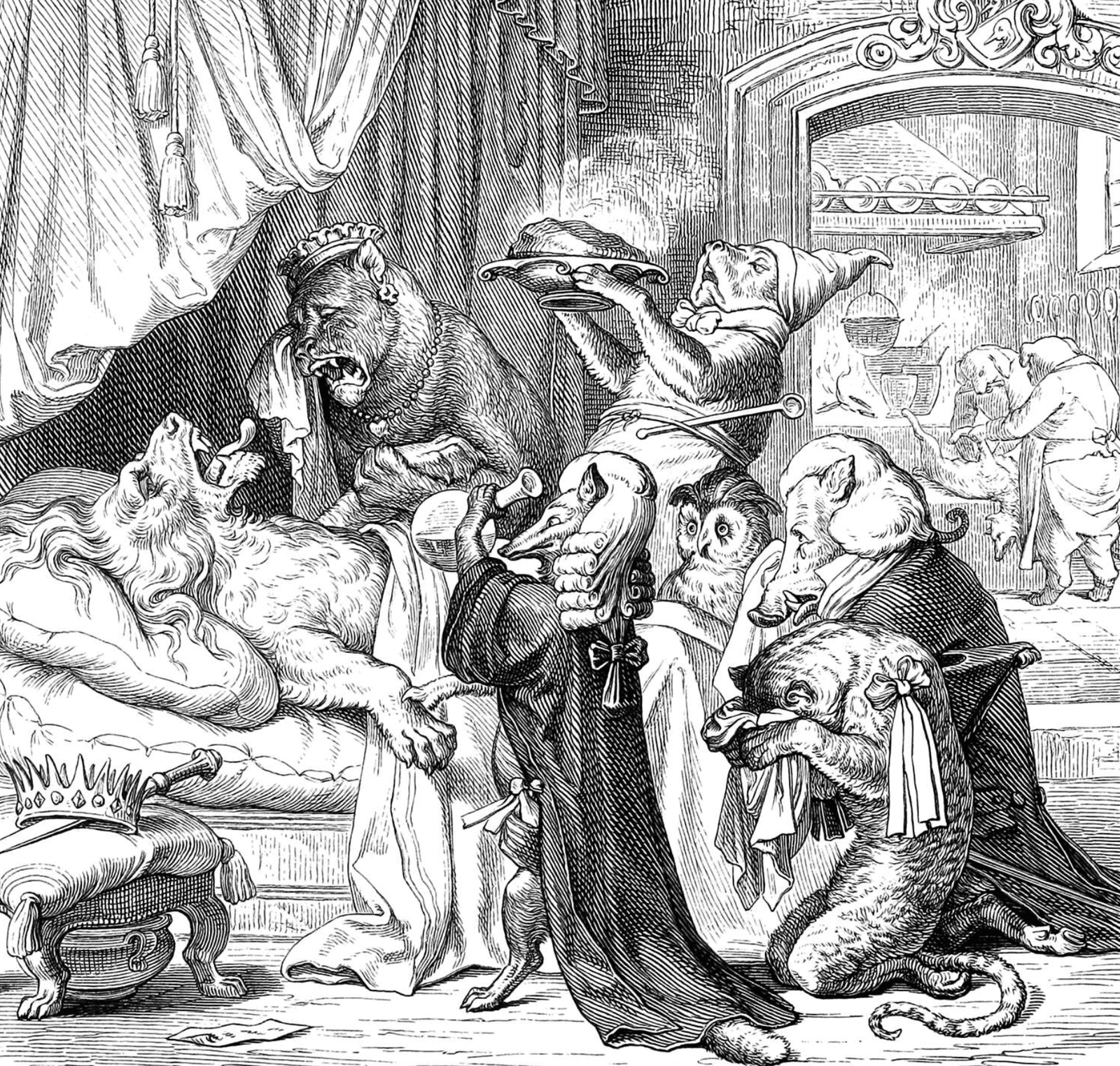

Think about it. If the definition of Christ’s Real Presence is so wide-ranging as to include the sense in which Paul VI meant “present” it in that context—which is to say, that Christ is present in the Church, especially in the acts of charity and the proclamation of the good news by all the faithful—it means that when we consume the “body of Christ” (again, not to be confused with the body of that antiquated Jesus fellow) we are eating not merely Our Lord but each other, a kind of perverse anthropophagic Alle Menschen werden Brüder. What Monsignor Irwin, by his confusion of categories and multiple shifting equivocations, seems to have arrived at is that in receiving Holy Communion you and I are consuming not only the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Our Lord Jesus Christ but also the body, blood, souls, and divinities (?) of all the baptized, of the faithful departed, of the saints triumphant in heaven, of Grandma Ruth.

Long-time readers of this publication will recall that in years past I have lamented what I called “the sad decline in heresy,” by which I meant the tendency of heresiarchs to forego bold cosmological speculation in favor of offering half-hearted defenses of various suburban moral schemas. Monsignor Irwin’s recent essay appears to be the result of not having considered what his arguments would mean when carried to their logical conclusion, but it is still a bold and decisive step in the direction of recovering what we have lost.

In a previous version of this article’s headline (though not in the body text), Monsignor Irwin’s title was misstated.